In the corridors of newsrooms, on the dashboards of independent publishers, and among SEO strategists around the world, a growing question is being asked: is Google quietly staging a slow‐motion killing of the web?

It’s not a conspiracy theory—it’s one grounded in shifting user behavior, shrinking traffic numbers, and high-stakes legal battles.

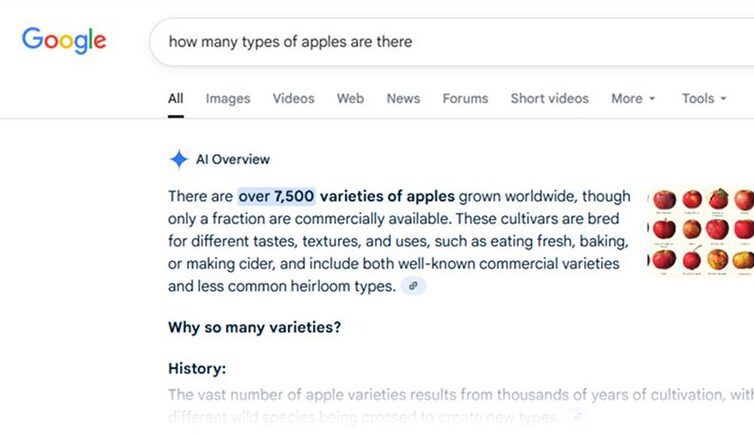

When you type a question into Google and it instantly spits back an AI-generated overview—without sending you anywhere else—that’s not just convenient. It’s potentially existential.

For users, it means faster answers. For content creators, it means fewer eyeballs, fewer ad impressions, and vanished revenue. For the broader public, it raises serious questions: who controls what knowledge we see, and who pays for it?

- In 2024, Google launched AI Overviews, which generates AI summaries and places them above traditional search results.

- In 2025, they introduced AI Mode, a search interface built more like a conversational chatbot than a list of links.

- These features aim to give users immediate, contextual answers without needing to click through to other sites.

By design or by consequence, these moves concentrate more of the search “experience” inside Google itself.

The evidence: traffic declines, click suppression, and publisher alarm bells

The story grows more troubling when you follow the numbers.

- Referrals down: Among prominent publishers, many report losses in Google-driven traffic between 1 % and 25 %. The median year-on-year drop in referrals for “premium publishers” was about 10 %.

- Click behavior changes: A Pew Research study found that when users see an AI summary, only 8 % click on a link—versus 15 % when they don’t see the summary. What’s worse: just 1 % of users click a link inside the AI summary itself.

- Zero-click searches boomin’: A growing share of Google searches apparently end without leaving Google at all—users get their answer from Google and stop. (This is sometimes called the “zero-click” phenomenon or “Google Zero”)

- Publisher lawsuits and complaints: Independent publishers have lodged antitrust complaints with the EU over the harm AI Overviews inflicts on their traffic and revenue. In the U.S., Chegg has sued Google, arguing that Google is “monopolizing” student queries by inserting AI Overviews above Chegg’s pages.

Google, meanwhile, counters that the aggregate traffic is relatively stable and that AI Overviews deliver “quality clicks”—visits from users more likely to engage meaningfully with content. Yet public data is limited, and many publishers claim reality is different from Google’s narrative.

Why this isn’t just a niche concern

When traffic losses are 10-25 % or more, this is often a blow that small or independent publishers can’t absorb. The largest outlets may survive on brand, subscription, or alternative channels. But niche creators, educational sites, and regional publications could falter.

AI Overviews work by ingesting content from across the web, summarizing it, and surfacing generated answers. That means your content may be reused without a click, without compensation, and without attribution—especially if it’s not “optimized” to be cited by the AI. Over time, it shifts the value proposition: why publish a full article if the summary will be presented without you harvesting ad or subscription revenue?

In traditional search, content creators could vie for rankings, backlinks, visibility. In an AI-first era, Google effectively becomes the gatekeeper: what part of your content gets summarized, what gets cited, and who gets traffic (if any) depends more on algorithms than on SEO or content quality alone.

The EU and UK are already scrutinizing Google’s AI search practices. The legal precedent could reshape how much influence tech platforms are allowed to exert over information distribution. Google’s defense—that the “open web is already in rapid decline” (cited in court filings)—feels nearly self-fulfilling.

The counterargument: is Google “killing” the Web—or evolving It?

Not everyone accepts the doom narrative. Google argues that:

- Users love faster answers and fewer clicks.

- AI Overviews still link to source content, encouraging deeper reading for many queries.

- Some types of content (forums, long-form pieces, specialty deep dives) are seeing increased visibility.

- Search behavior was already evolving (e.g. more mobile, more direct answer boxes), and AI is just the next step.

These points hold weight: Google has vast scale, and the incentive to keep a functioning web ecosystem remains (after all, Google’s ad business depends on it). But critics counter that Google’s margins and power let it operate asymmetrically: it can absorb harm that others can’t.

What this means for professionals, creators, and readers

- Journalists and editors may see harder hits in traffic—and more pressure to build direct relationships (via newsletters, apps, membership).

- Small businesses and bloggers risk losing discovery via search unless they adapt to AI citation norms (structuring content for “answer engines,” adding metadata). SEO may give way to a more specialized “AI-readiness.”

- Consumers get faster answers—but lose exposure to the “long tail” of voices, dissenting ideas, regional or specialized perspectives. Information becomes consolidated.

- Educators and researchers may find fewer outward links to source material, increasing the importance of verification, careful annotation, and insisting on original publication.

Google doesn’t seem to want the web to vanish. But what is emerging is an environment where the web becomes more of a resource to feed AI than a destination in itself.

The battleground now is: who gets to own the answer? Not just who ranks first, but who is cited in summaries. Not just who gets clicks, but who is allowed to participate in the new ecosystem.

If publishers do not adapt, if the regulatory push fails, the web may not die outright—but it will rewire itself into a structure where visibility is tightly controlled, and the incentive to create full content is weakened.

That’s not a future I’d call democratic.