Three years after ChatGPT burst into office Slack channels and dinner-table debates, a new analysis from Yale’s Budget Lab lands with a quieter message than the headlines predicted: the broad U.S. job market still looks… normal. Not frozen. Not in free fall. Just changing at roughly the pace it did during the PC and early internet eras. For workers wondering if the floor might give way and for managers deciding whether to reorganize teams around bots, that finding is a reality check, not a lullaby.

The Yale team combed through government labor surveys and compared the post-ChatGPT period with past technology shocks. They tracked how the mix of occupations shifts each month and looked for a telltale acceleration. It wasn’t there. The job mix has drifted only about a point faster than it did during the late 1990s internet boom, and much of today’s churn began in 2021 before generative AI tools took off. In other words, if your office feels different, it probably is, but not because the robots suddenly stole the org chart.

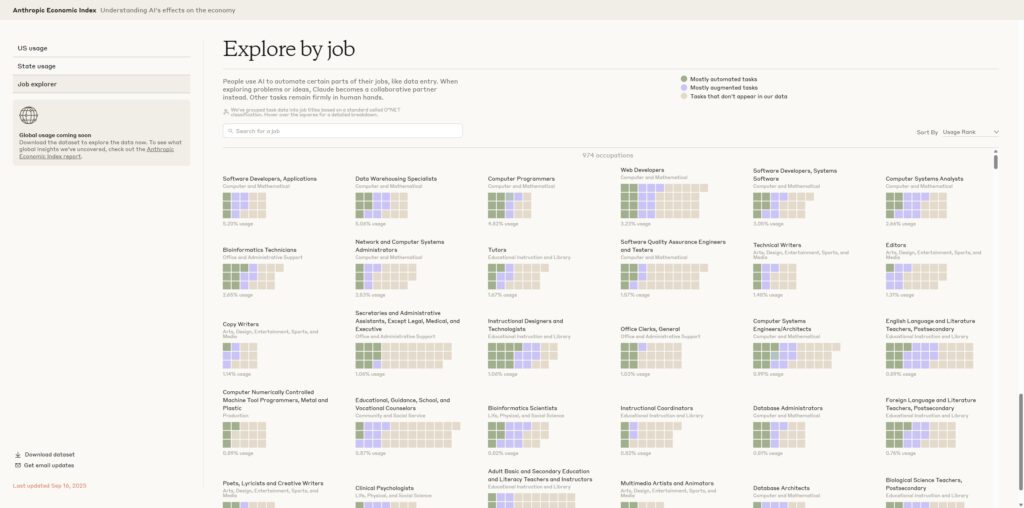

That might sound like good news. It also creates a different kind of tension. If AI is not erasing jobs en masse, then the real story is about who is getting a lift and who is getting left to figure things out without a map. The most intense usage today is clustered among coders and heavy writers. Anthropic’s new Economic Index, based on millions of anonymized Claude chats, shows adoption that is both rapid and uneven.

Some roles lean on AI to draft, debug, and summarize. Many other roles barely touch it. For now, the average AI interaction is still more of a teammate than a stand-in, with augmentation slightly outpacing automation in real usage data earlier this year. That skew could shift, but the pattern explains why entire occupational buckets have not collapsed.

If you are a recent grad, the picture is murkier but not catastrophic. Yale finds only small changes in how twenty-somethings are distributed across jobs compared with their late-twenties and early-thirties peers. Some months look bumpy, and unemployment for degree holders aged 20 to 24 touched the high single digits in late summer, but researchers say there is no clean line from generative AI to a collapse in entry-level hiring. A softer economy may be doing more of the work here than the bots.

Zoom out and history provides helpful humility. The fastest rewiring of America’s occupational mix happened in the 1940s and 1950s amid war and postwar shifts, not during any computer revolution. Compared with that upheaval, today’s changes remain sluggish, which suggests that if AI is truly a general-purpose technology it is likely to reshape work over years and decades rather than quarters. That timetable matters. It buys time for reskilling and smarter deployment, but it also tempts leaders to delay the hard decisions that make technology actually pay off.

For bosses, the message is not to relax. It is to get specific. OpenAI’s much-cited exposure work estimates that a large share of tasks could be sped up by AI, especially when you add software scaffolding around the model. Yet Yale’s labor-market lens finds no broad correlation between those exposure scores and real employment losses so far. The gap between potential and practice is exactly where productivity gains often stall. Companies that push AI into workflows with clear owners, training, and quality checks will capture value while laggards keep producing slide decks about pilots that never scale.

Workers should read the study not as a verdict but as a playbook. Where AI is being used, it is already changing the texture of daily tasks, from triaging customer emails to writing first drafts of RFPs or synthesizing research. That can mean higher ceilings for output if you are the one learning to pair with the tools, and it can also mean thinner justification for headcount growth if you are not. The data shows adoption is uneven across geographies and sectors, which implies opportunity for people and regions that move early. The jobs story ahead is likely to be less about disappearance and more about divergence.

Policy makers get a nudge here too. If mass displacement has not arrived, the useful focus shifts to measurement and diffusion. Anthropic has opened a window into real usage. Yale argues that all the major labs should publish privacy-safe data so economists can track where AI is replacing tasks and where it is lifting them, and then pair that with training dollars that target the lagging occupations, not just the loudest ones. That would turn today’s breathing room into a fairer ramp.

There is one more reason this matters. The public conversation has been shaped by confident forecasts on both extremes. Studies warning that 40 percent of jobs are threatened compete with claims that AI will create whole industries we cannot yet name. The Yale paper threads a simpler needle. It says the big shift is still ahead, and what we do between now and then will determine whether AI feels like a lift or a squeeze when it finally shows up in the aggregate numbers. If that future is built by the people already using AI to do their work better today, then maybe the quiet labor market of 2025 will look, in hindsight, like the start of something productive rather than a pause before a fall.