When DNS first became widely used in the 1980s, the system designers aimed for resilience and distributed caching. Over time, caching became central to DNS’s performance: resolvers would store query results to reduce load and latency. As a result, even though you update your DNS record on the authoritative server right away, the rest of the world doesn’t instantly “see” that update. Instead, they wait—sometimes minutes, sometimes hours—for old, cached data to expire. That delay is known colloquially as “DNS propagation.” But as we’ll see, propagation is really a matter of caches expiring, not records magically spreading.

In fact, DNS doesn’t push your change outward like a broadcast. Instead, recursive resolvers only ask (pull) when they receive a query. If a resolver already has the record cached and within its TTL, it won’t ask the authoritative server again. As Julia Evans puts it: “you’re waiting for cached records to expire, not for propagation” in the usual sense.

Because of this architecture, DNS changes may take time to appear globally, depending heavily on how long caches hold the old values. That said, “propagation” is still a useful shorthand when discussing how long until changes are broadly visible.

The mechanics: cache, TTL, resolver behavior

Time to Live (TTL) is king

Every DNS record includes a TTL (time to live), expressed in seconds. That TTL tells resolvers how long they may safely cache the record before discarding it and requesting fresh data. If you lower the TTL before making a DNS change, more resolvers will revalidate sooner, reducing the visible delay.

However, TTL is not absolute: some ISPs and resolvers may ignore or override TTLs, holding onto outdated records longer, which slows down appearance of your change.

Resolver and client caching

Caching happens at multiple layers:

- Your operating system, browser, or local DNS stub may cache results

- The recursive resolver (often operated by your ISP or configured DNS server) caches results

- Downstream DNS layers (intermediate caches) may also hold results

Until all these caches for your domain/IP expire, some clients will continue seeing the old data.

Changes you make to your primary authoritative DNS server must be synchronized to secondary (slave) nameservers via zone transfers. The frequency of this refresh is governed by SOA (Start of Authority) parameters (e.g. refresh, retry) in the zone file.

Moreover, when you change your domain’s nameservers (i.e. which DNS provider is authoritative), you involve TLD and root servers. Their caches must also refresh, which often carries longer delays.

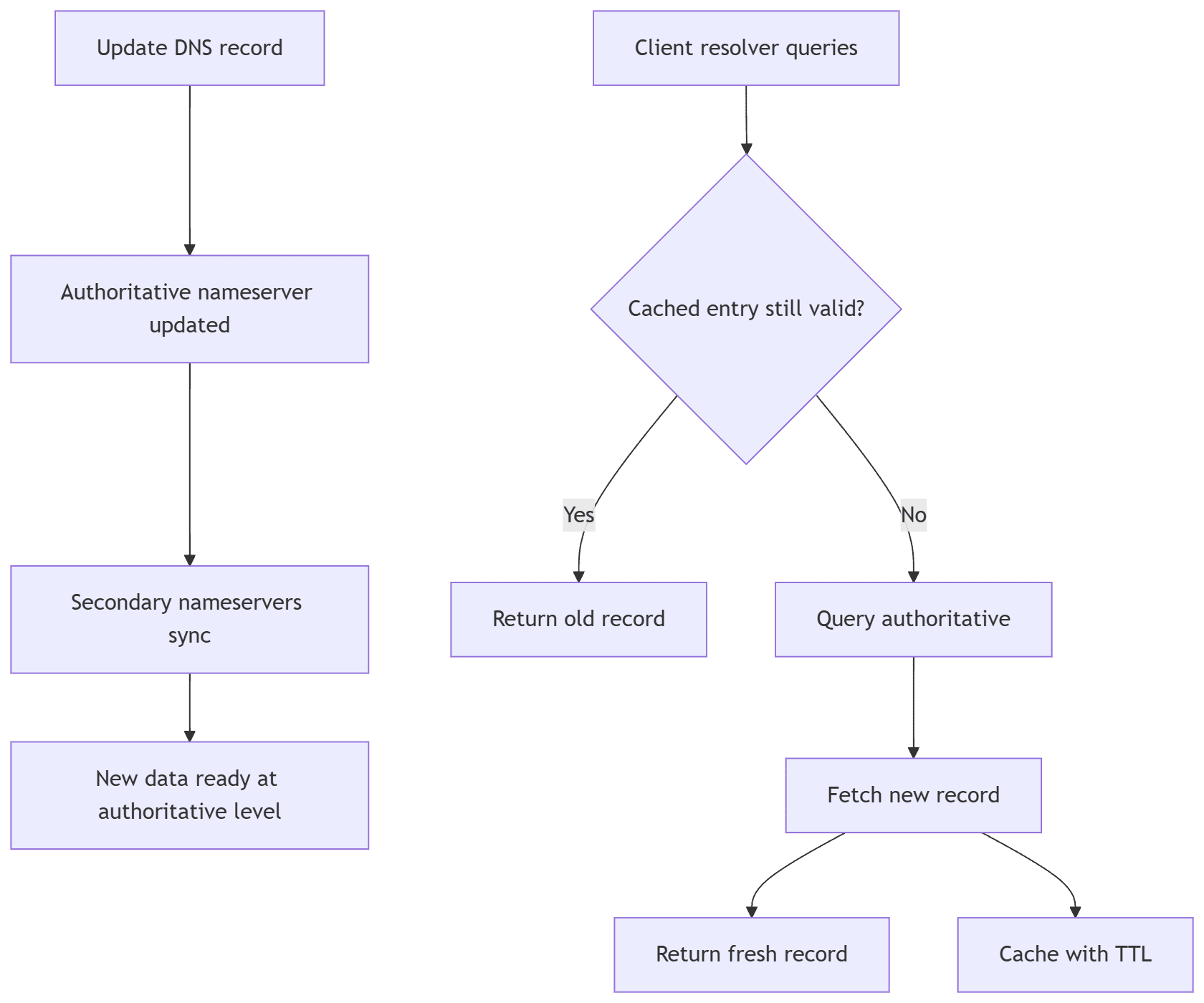

A mermaid view: the lifecycle of a DNS change

flowchart TD

Change[Update DNS record] --> Auth[Authoritative nameserver updated]

Auth --> Sec[Secondary nameservers sync]

Sec --> Ready[New data ready at authoritative level]

ClientQuery[Client resolver queries] --> Cache{Cached entry still valid?}

Cache -- Yes --> Old[Return old record]

Cache -- No --> NewQuery[Query authoritative]

NewQuery --> Fresh[Fetch new record]

Fresh --> Client[Return fresh record]

Fresh --> CacheStore[Cache with TTL]

This diagram encodes two fundamental truths:

- Your update takes effect immediately at the authoritative layer, but

- Clients may continue seeing old values due to caching until TTLs expire or caches flush.

Typical timeframes and variability

Although many guides quote “24–48 hours” for DNS changes, that is a rough upper bound, not a guarantee. In practice, many record changes (A, AAAA, CNAME) propagate within minutes or a few hours, especially if the TTL was low and caches are short.

However, certain cases take longer:

- Changes to nameserver (NS) records or transferring domains — TLDs and root servers are involved, caches are deep

- High TTLs (e.g. 24h, 48h) already in place before change

- Resolver policy quirks (ignoring TTLs) or network issues

- Intermediate caches that stubbornly persist

- Negative caching (absence of records being cached) with SOA-based minimum TTLs

Strategies to minimize delay and impact

Preemptively lower TTL

A common pattern is to lower the TTL a day or two before you expect to make changes (e.g. migration). This ensures caches expire faster when you do make the change.

Flush local caches

On your own system, forcibly clear DNS caches (OS, browser, local resolver) so you see the latest results.

Use multiple resolvers / check globally

Query external DNS servers around the world (e.g. dig @8.8.8.8 yourdomain or using DNS checkers) to see how far the propagation has reached.

Staged changes

If possible, set up a transition window where both old and new records coexist (e.g. dual‐stack or fallback addresses) so clients not yet updated can still reach the service.

Plan for NS changes carefully

Because nameserver changes often take longest, schedule such moves with ample buffer and avoid doing them at the same time as major record changes.