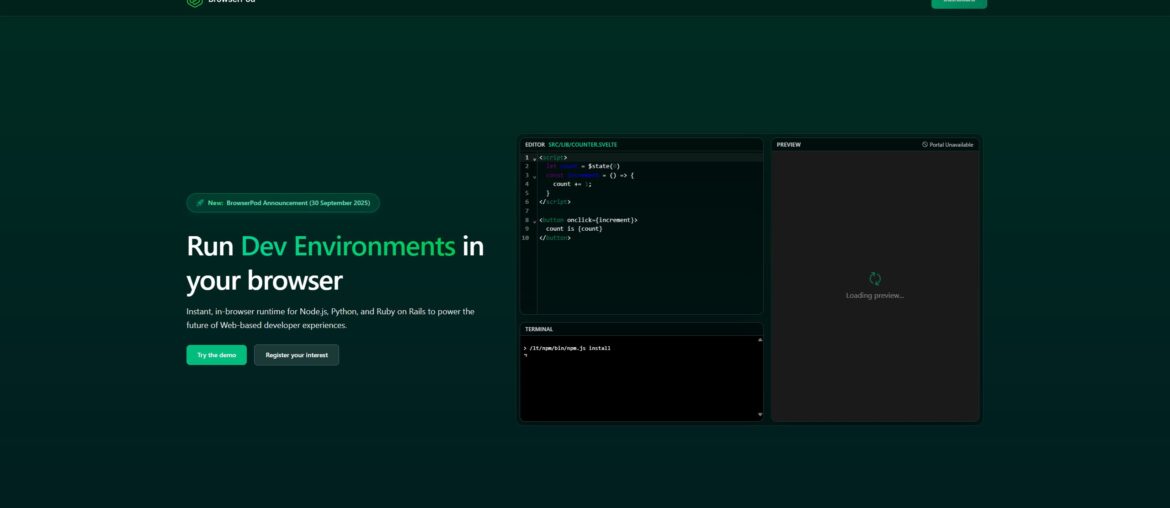

Imagine opening a browser tab and finding not just a web page, but a full development environment: runtime, server, preview, APIs, everything. No local installs. No remote server provisioning. Just code, immediately live.

That’s exactly what BrowserPod aims to deliver. It’s an in-browser “container” system built on WebAssembly (Wasm), intended to host full-stack development environments entirely client-side—with real networking, multiple runtimes, and external access.

If that sounds ambitious, it is. But the ambition is rooted in a solid foundation. Let’s walk through what BrowserPod is, how it works, what makes it interesting (and tricky), and where it might fit into the dev tooling ecosystem.

Here’s a plain way to see it:

- A Pod is like a container (you might think “Docker in the browser”) but entirely client-side.

- That container can run multiple processes (web servers, background jobs, databases) in parallel.

- The filesystem is virtualized, stored locally (in the browser), yet with block-style persistence.

- Networking: it supports inbound and outbound connections. You can expose HTTP/REST services running in a Pod to the outside world via something called Portals.

- It’s language-agnostic by design. Node.js is first on the roadmap; Python, Ruby (Rails) are coming.

In other words, BrowserPod aspires to make “run-your-app-locally” invisible — you just hit “Run” in your browser and everything spins up, with preview, APIs, and external access ready to go.

A practical use case: imagine an online IDE (say in a course, or a documentation site) where users can tinker with full-stack code, see real previews, and share a live URL instantly. No backends needed. That’s one of the target scenarios.

Under the hood (without getting lost in kernel weeds)

Of course, there has to be some serious engineering to make this fast and real.

Here’s a high-level sketch:

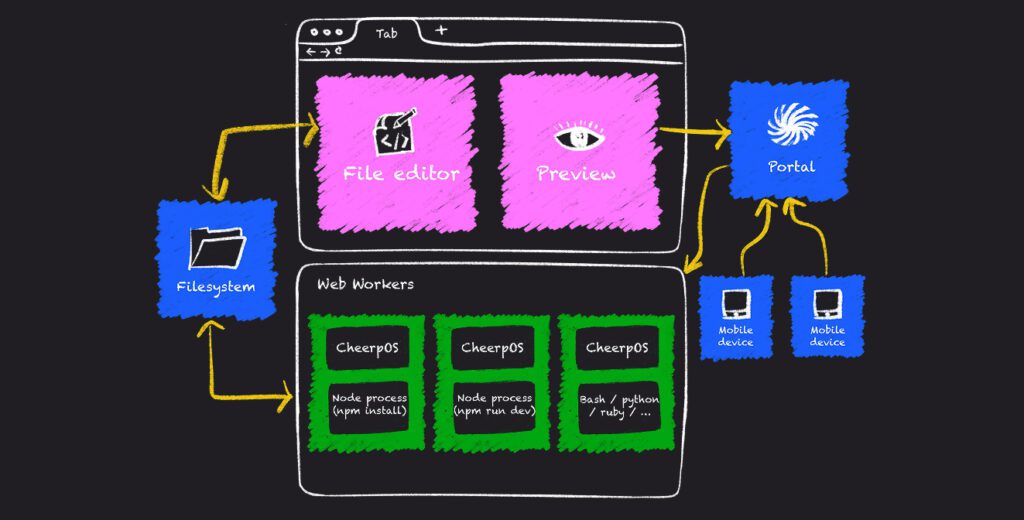

- CheerpOS kernel: At the heart, BrowserPod uses a kernel-emulation layer, internally called CheerpOS. It handles Linux system calls, filesystem operations, process scheduling, etc., inside a browser environment.

- WebAssembly + JS layering: For example, Node.js is compiled into Wasm + some JS glue, running atop CheerpOS. Other languages (Python, Ruby) will run purely as Wasm atop that kernel.

- Concurrency / parallelism: Pods can run multiple services in parallel, thanks to WebWorkers (browser threads). That gives “real concurrency” (well, plausible concurrency) inside the Pod.

- Portals / networking proxy: To let the outside world (or other devices) reach the HTTP endpoints inside a Pod, BrowserPod uses a portal/proxy mechanism. It handles mapping between the virtualized internal network and the external HTTP world.

- Storage & persistence: The filesystem is block-based and browser-local. It’s private to the Pod, but changes persist across reloads (within the browser).

This all means that when you restart a Pod, you don’t have to wait for a server to start up somewhere remote: the environment is re-spun inside your browser nearly instantly.

Now: there are limits. BrowserPod relies on certain browser features (for concurrency, memory sharing) that are not uniformly implemented across all browsers. For instance, Firefox doesn’t yet enable Atomics.waitAsync by default, which is needed. Also, Safari has quirks around JavaScript getters, global scopes, and this behavior that complicate compatibility.

Bottom line: as of now, BrowserPod works best in Chromium-based browsers (Chrome, Edge, Brave). Wider support is in the works.

Why this matters

At first glance, it may sound like “just another way to run code in the browser,” but I think BrowserPod opens up a few meaningful shifts. Here are some of them:

Zero setup, instant feedback

If developers don’t need to install anything, configure local Docker, manage version mismatches, or fear “it works on my machine but not yours” — that’s a big win. You just open a browser, everything is ready. Think: teaching environments, coding bootcamps, tutorials, documentation with live examples.

Better alignment between dev and prod

Because BrowserPod uses high-fidelity runtime compilation (Wasm + kernel emulation), the behavior inside a Pod is meant to mirror how the app will run in production. That reduces surprises when you “move it out of the browser.”

Shareable, live previews

Thanks to Portals, you can expose HTTP endpoints from inside your Pod to external users or devices. Want to show your progress to a client, ask someone to test on mobile, or embed a demo in docs? That becomes trivial.

Support for AI agents & secure sandboxing

One of the stated target use cases is embedding “agents” (e.g. AI assistants) that operate on code, directly in the browser. Because everything runs client-side and sandboxed, risks from supply-chain attacks or remote execution are reduced.

Language flexibility

Unlike some container-in-browser solutions tied to one runtime, BrowserPod is built from the start to support multiple languages and stacks (beyond Node). That gives it more flexibility and future-proofing.

So yes — for beginners, this could mean easier learning curves, less friction. For seasoned devs, it means faster iteration and alignment.

Challenges, caveats and hurdles (because there are some)

I don’t want to overhype—there are real constraints and questions ahead. Some of these are technical, others social or ecosystem-based.

- Browser compatibility: As mentioned, current support is best for Chromium browsers. Firefox and Safari have gaps. Some users on Hacker News pointed this out: > “This demo requires a Chromium-based browser… Firefox is currently unsupported due to Atomics.waitAsync…”

- Proprietary / licensing concerns: BrowserPod is not open-source (at least initially).

- Resource constraints: Running many processes, memory usage, thread limits — inside a browser — will hit limits. The browser sandbox architecture imposes caps.

- Security & isolation: Emulating system calls and exposing services raises concerns about isolation. Ensuring that Pods don’t accidentally leak or collide is tricky.

- Persistence & storage limits: Browser-based storage (IndexedDB, filesystem APIs) has quotas and behavioral differences across browsers and OSes.

- Scaling & production readiness: While dev environment parity is great, for large apps or heavy loads, the browser environment may not suffice. You’ll likely still need backend infrastructure.

- Ecosystem adoption: For BrowserPod to succeed, it needs tooling integration (editors, CI, deployment workflows) and developer trust.

One developer in Hacker News commented: “this would be good … if the UX allows for it … especially when all you’ve got are Chromebooks.” That nails one sweet spot: when local setup is hard (e.g. in education, on cheap devices), BrowserPod shines.

How BrowserPod compares to alternatives (e.g. WebContainers, WebVM, etc.)

To better situate BrowserPod, it helps to compare with existing in-browser or virtualization tooling.

- WebContainers (by StackBlitz, etc.): This is a similar idea (in-browser Node environments). BrowserPod positions itself as more flexible (multi-runtime) and with inbound networking (allowing external access).

- WebVM: That’s Leaning Technologies’ own Linux-in-browser environment (via WebAssembly) used in other projects. BrowserPod sits on a kernel layer partially evolved from that technology (CheerpX) and extends it for container-style isolation and multi-service workflows.

- Remote dev containers / cloud IDEs: Tools like GitHub Codespaces, Gitpod, Replit allow remote environments but require server infrastructure. BrowserPod’s advantage is that those servers are not needed (for many use cases).

- Docker + local dev: The classic choice. More control, more resource access. But also more setup, dependencies, versioning complexity. BrowserPod doesn’t replace Docker fully — but it lowers the barrier for many workflows.

So BrowserPod is not just another container in browser — it’s trying to fuse the convenience of browser tooling with serious runtime fidelity and network exposure.

When & where BrowserPod might shine

Here are some concrete scenarios where BrowserPod could be particularly helpful:

- Coding tutorials and educational platforms

Students can instantly run full-stack apps in the browser, tinker, see live previews, and share URLs. No setup hurdles. - Interactive documentation / “live code” docs

API docs, SDKs, product docs could embed real working environments. You try code in the browser, backed by a full backend. - Prototyping / MVPs

You hack quickly, share a live link, gather feedback — without spinning up servers. - Low-code / no-code tools with logic modules

If a no-code tool allows custom modules, BrowserPod could host those modules in-browser, reducing backend costs. - Agent-based tooling

Where AI agents or plugins operate on code locally in a sandbox, reducing remote dependencies or security risk. - Hackathons / workshops / demo apps

You don’t need participants to install anything — just open a link, start coding.

But there are also places where it won’t (yet) replace traditional workflows: large-scale production apps, heavy computation workloads, data-intensive tasks, or environments needing direct hardware or privileged access. BrowserPod is most exciting in the “developer environment / sandbox / preview / small-to-medium apps” domain.

The bigger picture: what this means for dev tooling’s future

Brace yourself: BrowserPod suggests a future where:

- Dev environments are more ephemeral, more browser-native than remote or local installs.

- The boundary between “writing code” and “trying it live” becomes thinner.

- More parts of the stack (backend, frontend, agents) can run in-browser securely, reducing friction.

- Tooling companies might compete less for “cloud servers” and more for smart client-side environments.

- Education, onboarding, and code sharing might shift heavily toward “instant start in browser.”

Of course, this future depends on overcoming browser limits, ensuring security, and embedding gracefully into developer ecosystems (CI/CD, deployment, etc.). But BrowserPod is one of the bold early bets pushing in that direction.

Final thoughts

When I first read the BrowserPod announcement, I thought, “Isn’t that just another WebContainer clone?” But as I peeled back the layers, I realized its ambition is more expansive: multiple runtimes, inbound networking (Portals), high-fidelity kernel emulation, and agent hosting. If it works well, it could shrink friction in dozens of dev-adjacent domains.

Still — it’s early. I’m cautious about compatibility, performance, and adoption. Will developers trust a browser sandbox for serious backend logic? Will edge cases (e.g. large file I/O, memory limits) bite? But the potential is real.

If you’re a beginner or tinkerer: keep your eyes on BrowserPod, try the demo when it’s live, and see whether live coding fully inside a browser is more than just a novelty — whether it feels like the real deal.