If you run a Linux server for more than an afternoon, you’ll want things to happen without you staring at a terminal: rotate logs, ship backups, sync files, pull metrics. cron is the small, stubbornly reliable scheduler that’s been doing that on Unix since the 1970s. It reads a table of times and commands, wakes up every minute, and runs what’s due. We’ll walk through how to think about cron, how to write schedules that behave, and how to debug them when they don’t. You’ll need a Linux machine you can SSH into; a tiny Droplet from DigitalOcean is perfect, and the examples below assume a Debian/Ubuntu-like system with systemd, which we’ll note when it matters.

What cron actually runs

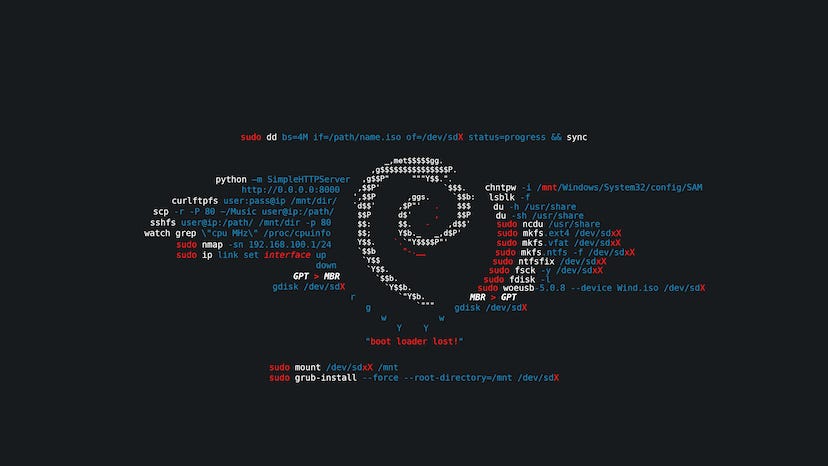

Cron doesn’t run “your terminal.” It runs commands in a non-interactive shell with a minimal environment. That means your aliases aren’t loaded, your PATH is shorter than you think, and anything that depends on a login shell might fail. Start by checking which cron you have and how it’s started, because that determines a few defaults.

crontab -V

ps -ef | grep crond

systemctl status cron || systemctl status crondOn Debian/Ubuntu, the service is usually cron; on RHEL/Alma/Rocky it’s crond. If the service is inactive, enable it now so your jobs can run after reboots too.

sudo systemctl enable --now cronFiles and scopes

There are two broad places to put schedules: the per-user crontab and the system crontabs. Use your user crontab for most automation tied to your account. Use system locations for machine tasks or when you need a specific user or environment.

# per-user crontab (invokes your editor)

crontab -e # edit

crontab -l # list

crontab -r # remove (careful)

# system crontabs (root only)

sudoedit /etc/crontab

sudo ls -l /etc/cron.d /etc/cron.hourly /etc/cron.daily /etc/cron.weekly /etc/cron.monthly/etc/crontab and files in /etc/cron.d/ include an extra user column, letting you specify who runs the command. The cron.* periodic directories are for drop-in scripts; a helper like run-parts executes every executable file there on its cadence. We’ll come back to these when we talk about hygiene.

The crontab line format

Every job is one logical line: five time fields, then the command. The fields are minute, hour, day-of-month, month, day-of-week.

# ┌──────── minute (0–59)

# │ ┌────── hour (0–23)

# │ │ ┌──── day of month (1–31)

# │ │ │ ┌── month (1–12 or JAN–DEC)

# │ │ │ │ ┌─ day of week (0–7 or SUN–SAT; both 0 and 7 mean Sunday)

# │ │ │ │ │

# * * * * * command-to-runYou can use lists (1,15,30), ranges (9-17), steps (*/5), and names (MON-FRI). The day-of-month and day-of-week fields are OR’d unless you use cronie’s AND extension; assume OR unless you know your implementation. That matters if you schedule on “the 1st and Monday” and only want the intersection.

# every 5 minutes

*/5 * * * * /usr/local/bin/healthcheck

# 02:30 every day

30 2 * * * /usr/local/bin/backup

# 03:15 on weekdays

15 3 * * MON-FRI /usr/local/bin/reportMost implementations also support nicknames like @reboot, @hourly, @daily, @weekly, and @monthly. @reboot is handy for services that don’t need full systemd units.

@reboot /usr/local/bin/warm-cacheEnvironment, PATH, and the shell

Cron’s environment is small. Fix three things up front: pick the shell, set a real PATH, and set a working directory if the script expects one. These go at the top of your crontab.

SHELL=/bin/bash

PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin

HOME=/home/youruserThen make sure every script has a shebang and behaves the same whether run by cron or by you.

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -euo pipefail

cd /opt/app

/usr/bin/python3 manage.py dumpdata > /var/backups/app.jsonIf the job needs a Python virtual environment or Node toolchain, activate it inline or call the absolute path to the interpreter.

# Python venv example

15 1 * * * cd /opt/app && . .venv/bin/activate && python scripts/rotate.pystdout, stderr, and mail

By default, cron captures a job’s output and emails it to the job’s owner (or to the address in MAILTO=). On many cloud images, local mail isn’t set up, so you never see failures. Decide where the output goes.

# send all job mail to a real address (works if local MTA is configured)

MAILTO=ops@dropletdrift.com

# otherwise, redirect output explicitly

30 2 * * * /usr/local/bin/backup >>/var/log/backup.log 2>&1Keep logs concise or rotate them with logrotate. If you don’t want routine “nothing happened” noise but still want errors, drop stdout and keep stderr.

*/10 * * * * /usr/local/bin/scrape 1>/dev/nullIdempotence and locking

Cron will happily start a new run even if the previous one is still working. That’s fine for idempotent tasks; it’s dangerous for backups and imports. Use filesystem locks to serialize runs.

# use flock to prevent overlap

*/5 * * * * flock -n /var/lock/scrape.lock /usr/local/bin/scrape >>/var/log/scrape.log 2>&1If your distro doesn’t ship flock in PATH, find it:

command -v flock || sudo apt-get install -y util-linuxFor jobs that must run eventually but not at a specific minute, you can schedule frequently with a lock and let the job self-throttle. That reduces the risk of missed runs during reboots.

Health checks and exit codes

Cron considers any output worthy of email; it doesn’t care about exit codes except to set the job’s status. Your job should exit non-zero on failure and zero on success, and it should emit a one-line summary that a human can read in a mailbox or log. If you use a monitoring service, add a ping on success and a different ping on failure.

/usr/local/bin/backup && curl -fsS https://hc-ping.com/UUID > /dev/null || echo "backup failed" >&2Remember: if you silence both stdout and stderr, cron has nothing to mail, and failures vanish. Keep at least one signal.

System crontab vs /etc/cron.d vs run-parts

System-wide jobs belong to root and should live where configuration management can track them. /etc/crontab is fine for a couple of lines, but /etc/cron.d/ scales better for packages and tools. Each file in /etc/cron.d/ uses the 6-field syntax (time fields plus user), and you can keep one file per component.

# /etc/cron.d/backup

# min hr dom mon dow user command

30 2 * * * root /usr/local/bin/backup >>/var/log/backup.log 2>&1The periodic directories (/etc/cron.hourly etc.) are executed by run-parts, which only runs executables with simple names. Don’t put dots, extensions, or spaces in filenames there.

sudo install -m 0755 my_daily /etc/cron.daily/my_dailyIf you need precise timing (e.g., 02:17 daily), skip the periodic directories and write an explicit schedule instead. The periodic bins run at distro-defined times that may drift or be randomized.

Practical examples you can copy

A daily database dump with retention:

SHELL=/bin/bash

PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin

MAILTO=ops@dropletdrift.com

# 02:15 dump, keep 7 days

15 2 * * * flock -n /var/lock/pg_dump.lock /usr/local/bin/pg_dump.sh >>/var/log/pg_dump.log 2>&1/usr/local/bin/pg_dump.sh:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -euo pipefail

TS=$(date +%F)

OUT=/var/backups/pg/db-$TS.sql.gz

pg_dump -h /var/run/postgresql -U app dbname | gzip -9 > "$OUT"

find /var/backups/pg -type f -name 'db-*.sql.gz' -mtime +7 -delete

echo "backup ok: $OUT"A five-minute scraper that should never overlap and should time out after 2 minutes:

*/5 * * * * timeout 120s flock -n /var/lock/scrape.lock /usr/local/bin/scrape >>/var/log/scrape.log 2>&1A weekly cert renewal that only runs if the binary exists:

0 4 * * 0 test -x /usr/bin/certbot && certbot renew --quiet --deploy-hook "/usr/local/bin/reload-nginx"A reboot task that warms caches and then exits:

@reboot /usr/local/bin/warm_cache >>/var/log/warm_cache.log 2>&1Debugging “cron runs it differently”

When something works by hand but not in cron, start by capturing the environment and working directory inside the job. You want proof of what cron saw.

# debug stub

env | sort > /tmp/cron.env

pwd > /tmp/cron.pwd

which python > /tmp/cron.which 2>&1Compare those files to your interactive shell and fix PATH, HOME, or the working directory. If output email is missing, redirect stderr to a log and watch for errors. If the job depends on network or services, add a small delay after reboot jobs or add service checks.

@reboot sleep 10 && /usr/local/bin/startupOn systemd systems, cron logs often land in the journal. Read them to confirm the scheduler saw your line.

journalctl -u cron -u crond -fIf you still can’t see your command firing, check for non-ASCII characters, carriage returns from Windows editors, or a missing newline at end of file. Cron is picky.

Time zones, DST, and missed jobs

Cron reads the system time zone unless you set CRON_TZ= in some implementations. For servers, keep the OS clock in UTC and do local time conversions in your application. Daylight saving transitions can skip or duplicate a local hour; UTC avoids that ambiguity. If the machine sleeps, classic cron may miss runs; anacron complements cron by ensuring “once a day/week/month” jobs eventually run.

# anacron installs and schedules daily/weekly/monthly catch-up jobs

sudo apt-get install -y anacron

sudo systemctl enable --now anacronIf you need guarantees and sophisticated calendars, consider a systemd timer or a real job runner. We’ll compare briefly next so you can decide.

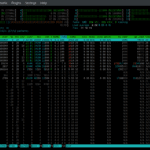

When to use a systemd timer instead

systemd timers integrate with service units, support calendar expressions like “Mon..Fri 03:00”, and handle persistence and missed runs with Persistent=true. They’re a good fit for long-running services or when you already manage units. Cron wins on simplicity and portability. If a job should run “03:00 even if the host rebooted at 02:59,” a timer with persistence is less foot-gunny than cron plus @reboot.

A minimal timer plus service looks like this:

# /etc/systemd/system/report.service

[Unit]

Description=Nightly report

[Service]

Type=oneshot

User=report

WorkingDirectory=/opt/report

ExecStart=/usr/bin/python3 generate.pytimer:

# /etc/systemd/system/report.timer

[Unit]

Description=Nightly report schedule

[Timer]

OnCalendar=03:15

Persistent=true

[Install]

WantedBy=timers.targetEnable the timer:

sudo systemctl daemon-reload

sudo systemctl enable --now report.timer

systemctl list-timers | grep reportIf you’ve followed along, you already have the intuition to pick between cron and timers based on durability needs.

Security and least privilege

Run jobs as the least-privileged user that can do the work. If a command needs root, consider granting a single sudo rule instead of handing the whole job to root. Also be careful with unquoted expansions and world-writable paths, because cron runs unattended and will happily execute whatever the shell resolves.

# /etc/sudoers.d/backup (edit with visudo)

backup ALL=(root) NOPASSWD: /usr/local/bin/backupThen schedule as the backup user and call sudo /usr/local/bin/backup. That limits blast radius. Rotate credentials out of the crontab and into protected config files or the environment of your script.

Hygiene: keep crontabs boring

Crontabs that age well share a few traits. They use absolute paths, they centralize environment lines at the top, they redirect output consistently, and they push multi-step logic into versioned scripts in /usr/local/bin/ or your app repo. The crontab remains a readable schedule, not a shell playground. When you come back six months later, you’ll thank yourself.

A tidy example that pulls several ideas together:

SHELL=/bin/bash

PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin

MAILTO=ops@dropletdrift.com

HOME=/home/app

# backups

15 2 * * * flock -n /var/lock/backup.lock /usr/local/bin/backup >>/var/log/backup.log 2>&1

# metrics (quiet unless error)

*/5 * * * * /usr/local/bin/push-metrics 1>/dev/null

# reports (Python venv, no overlap)

0 6 * * MON-FRI cd /opt/report && . .venv/bin/activate && flock -n /var/lock/report.lock python run.py >>/var/log/report.log 2>&1Quick checklist before you log out

Confirm the service is enabled, the schedule is correct, and the job can run headless. Make sure logs go somewhere you actually read. Add locking where overlap is dangerous. Prefer scripts over inline one-liners. If you’re deploying to a new Linux box (a small DigitalOcean Droplet works well), test one representative job with an every-minute schedule, watch it fire, then dial back to the real cadence. That way your first failure happens on purpose, while you’re still looking.